Brexit: Another Tile in a Broader Mosaic

It is easy to lose one’s bearings untangling the possible political permutations following “Brexit,” the United Kingdom’s recent decision to proceed down the path of secession from the European Union. While the politics of the Brexit referendum aftermath are extremely complicated, the underlying message, in our minds, is simple: the EU is falling short on its promises of widespread prosperity driven by tighter integration. We see the vote as one more piece in an evolving mosaic whose broad theme is a rise in economic populism or, said differently, a pushback against globalization. The success of the Brexit camp is likely to encourage and invigorate other such campaigns in countries like France and Italy. Although the barriers to exit are high and quite real, they are not insurmountable, and the resulting cascade of uncertainty cannot help but have economic consequences.

For the past three decades, global asset valuations have benefited from a succession of favorable events that served to facilitate the free flow of capital, labor, and goods around the planet. From the collapse of the former Soviet Union to the formation of the European Union to the entry of China into the World Trade Organization, the world marched unflinchingly down the path of increased globalization. While there has undoubtedly been great wealth created, and general living standards have risen, so too have measures of inequality and numbers of displaced workers. Discontent has been building over the past few years as the recovery from the financial crisis of 2008 has been disappointingly shallow. That displeasure has most recently manifested itself in a turn to anti-establishment politicians such as Donald Trump, Bernie Sanders, Boris Johnson, and Marine LePen, with negative implications for global growth.

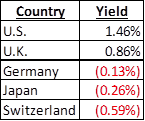

The world is already struggling to generate nominal growth, and any new obstacles to the flow of capital, labor, and/or goods will only serve as added ballast. With interest rates at or near all-time lows in almost every country, there is no room for traditional monetary stimulus. Instead, central banks have been forced to experiment with quantitative easing or debt monetization or “helicopter money,” with the early returns suggesting failure (for example, in Japan). That puts the onus on fiscal stimulus during a fraught political period which reduces the odds of sufficient action, though eventually governments may be forced to spend.

In sum, our takeaway from the Brexit vote is that growth will likely remain in short supply for the next few years, with interest rates feeling the gravitational pull of the search for income in a growth-starved world. We could see valuations of income-producing assets reach historic extremes, and stocks levered to taxpayer funded infrastructure projects should fare well, while economically-sensitive assets that produce little or no yield could remain out of favor for some time. Although nominal interest rates have fallen sharply, so too have inflation expectations, which means real returns to investors can still be positive. But very low interest rates also mean that small swings in the economic outlook can produce very large movements in asset prices; investment decisions will need to be made with a calmness belying the volatility. Disciplined asset allocation will be a key determinant of future returns.

Table 1. Select 10-year government bond yields (as of 7/1/16)